(Note: this article has content through Memorial Day except where easily updated but may run at a later date. The conclusions aren’t going to be any different, and the 2-0 loss to the Phillies in which the Braves didn’t barrel anything, struck out looking three times, and only had one ball hit over 300 feet kind of reinforces the points here. Also, this post is really f’n long. Sorry not sorry.)

The Atlanta Braves are no stranger to slow starts. 2024, which became a five-month slog after the Braves started as the best team in baseball, was more the exception. I’ve been watching the Braves since 2001 — they didn’t get above .500 for good until June of that year. In my time, I’ve seen 14 Braves playoff teams, and of those, only six led the division by the end of May. (Of course, not all 14 of those teams won the division, but you get a similar ratio whether you use above .500, in line for a playoff spot, and so on.) The Braves currently sit at 25-28, something multiple rungs below the catbird seat, with the vibes likely dampened not just by the record, but by the fact that 2024 was not much fun either. If last year were 2022 — a year in which the Braves were actually 23-27 when May ended — maybe there’d be more leeway to the slow start. The vibes are the vibes, though.

But, the vibes are also at least partially informed by reality. Pure animal spirits, they are not. When the season started, the Braves were handily projected to be baseball’s second-best team. The Steamer-ZiPS mix had the point estimate as about six games ahead of the Phillies; ZiPS alone had them as tied for the prospective division lead, which tells you something about how Steamer and the FanGraphs methodology pegged the Braves, if nothing else. As of May 28, though, the current 25-28 club is only projected to finish with baseball’s eighth-best record. This isn’t a reflection on talent (more on that in a bit), but a reality that the Braves currently have baseball’s ninth-worst record. They’re in a hole, basically. The Orioles are the only contender to have a rougher start to the year relative to expectations; no team but the Os has shed more in playoff odds, and no team has shed more in division or championship odds. The Braves currently have somewhere between five-in-ten and six-in-ten playoff odds and division odds of one-in-ten, and that’s from the favorable projection system; I don’t know what ZiPS has right now, but it had them even worse after a 9-14 start, so… yeah. Whether you find solace in the fact that the FanGraphs ZiPS-Steamer blend still has them in line for the NL’s second Wild Card spot is purely a personal matter.

It’d be one thing if the Braves were losing in a fundamentally “That’s baseball!”-esque way. Any team can undershoot its talent level for a month, or even two months. If I’m remembering correctly, the 70-game mark is about the point where a team’s record is influenced equally by random baseball happenings and talent, and 53 is considerably less than 70. The problem, though, is that they’re not. This isn’t a team undershooting its run differential or having weird sequencing problems. It’s just a team that hasn’t been particularly good at anything. I don’t think teams need an identity — they just need production — but if the Braves had an identity, it’d be something oriented around existing, like a shy middle schooler at a social event of yesteryear (these days everyone is just on their phones all day and there aren’t even events, right?). I’ll go through this in more detail, but fundamentally, the current Braves are:

- 14th in position player value, including 17th in offensive value;

- 12th in hitting inputs as measured by xwOBA;

- 23rd in pitching value, split between 20th in rotation value and 25th in bullpen value; and

- 132h in pitching inputs as measured by xFIP- (split between eighth and 17th between the rotation and bullpen, respectively).

Those are the rankings of a pretty nondescript team. The hitting is meh (has “mid” replaced “meh?” you tell me), the pitching is worse but the inputs are also meh/mid, so it’s not that exciting. The only thing that’s remarkable? The team currently ranks third in defensive value (yay) — however, because we assign defensive value on a positioning-neutral basis these days, the team’s actual conversion of fieldable balls to outs drops to seventh, which is still good, but not bailing out the hitting and pitching. (Thanks, Nick Allen!)

I’m 750 words in, but nowhere near done. For the rest of this post, I want to touch on some specific hitting and pitching issues that I think are endemic to this iteration of the team, and then I want to loop back around to certain high-level elements that bum me out vis-a-vis the slow-starting Braves teams of years past. Read on, or skip to the comments, whatever.

The offense, such as it is

I’m not going to relitigate the whole “are the Braves using a new offensive approach and if so, what times are they or aren’t they” thing here. If you disagree, too bad, skip this section. It’s happening, at least sometimes, and the fits-and-starts nature of it makes it hard to talk coherently about it. But, I’m going to talk holistically about the team’s offensive performance, anyway, even though I know it includes a bunch of things that have only been true for stretches. We don’t know what the team is going to do going forward, anyway.

During the offseason, in Spring Training, and over the first month of play, we heard a number of things from the team’s coaches: (1) scoring runs “in lots of different ways”; (2) a greater emphasis on walks; and, (3) the players apparently having an internal chase rate contest. The rationale for each of these makes some sense — MLB’s own measurements indicate that in 2025, the baseball has more of a drag coefficient than ever before. In practice things have played out pretty similarly to 2024; I won’t get into a tangent here about how MLB appears to have increased both the coefficient of restitution, i.e., how “springy” the ball is as well as the drag coefficient, leading to a strange situation where swinging harder is rewarded but then also punished if the ball catches substantial hangtime, but this, too, is clearly happening. Further, we learned earlier this season that MLB has changed how it gives feedback to umpires, and therefore, that the strike zone has effectively shrunk. If you were concerned about the Braves’ poor-relative-to-the-league outcomes on barrels in 2024 (25th in hit rate on barrels, 21st in rate of homers on barrels) and also concerned about Goodheart’s Law (I guess? I don’t know), I can see why you might want a change.

And boy, have we got a change. The current Braves team does not rank in the top ten in wOBA, xwOBA, or barrel rate. They are not in the top five in hard-hit rate, and barely in the top five in average exit velocity. Their lowest previous ranks in those stats, going back to 2019, when they implemented the teamwide approach to attempt to murder the ball in the first place?

- wOBA: 12th (2024)

- xwOBA: 7th (2024)

- Barrel rate: 3rd (2019. 2021)

- Hard-hit rate: 8th (2019)

- Average exit velocity: 10th (2019)

We can go deeper. The team currently ranks 11th in swinging at pitches in the zone, 12th at not chasing, ninth at not whiffing overall, tenth at making contact on pitches in the zone, and 27th at swinging at the first pitch. Again, it’s pretty nondescript, except that they love taking the first pitch. This is a dramatic turnaround from, again, closest rank going back to 2019:

- Z-swing: 3rd (2019) – compare to 11th now

- Avoiding o-swing: 14th (2019) – compare to 12th now

- Avoiding whiff: 9th (2019) – compare to 9th now

- Z-contact: 22nd (2023) – compare to 10th now

- First-pitch swing: 6th (2023, 2024) – compare to 27th now

The Braves previously swung a lot, including on first pitches, and didn’t worry about missing. The Braves now… you can’t really describe them, except that they take first pitches. (Note: anyone who says the Braves adjusted because the league adjusted is likely missing the point. The Braves did the same thing all those years and largely only improved until 2024. Even amid injury, the offensive approach in 2021 was about as blatant as it was in the years after.)

We also have bat speed and bat tracking data now, though only for part of 2023 and the subsequent seasons. In 2023, the Braves were first, by a longshot, in swing speed and the rate of swings above 75 mph. In 2024, they were still tied for first in the former (yes, amid the injuries) and still first by a longshot in the latter. In 2025 so far, they’ve fallen to ninth and second. Oh, but sure, Alex Verdugo is on the 2025 Braves. Should we do it by player? Yep. Click if you dare. I’ll spare you the visual: every single regular’s bat speed declined from 2023 to 2024, and then again from 2024 to 2025, as did their rate of 75+ mph swings — the only exception is that Marcell Ozuna’s swing speed is a bit above 2024. Sean Murphy is swinging slower despite being further removed from his oblique injury. The only guys not affected, even when you cut down the minimum number of swings needed, are Jarred Kelenic and Eli White — even Ronald Acuña Jr. shows the same pattern, and he’s only been around for three games and like 15 swings. Most guys have also moved back in the box, with intercept points coming further back (not Ozuna or Riley). Most of their swings are flatter and more opposite-field oriented, though there are exceptions, here and there. I’ll save you all the digging — Olson and Ozuna look like they get it and are are thriving, and everyone else is in woof territory.

Back to the point, though. The Braves made these changes to chase less, walk more, and “score runs in different ways.” Are they doing it? You already know the answer, and it’s a resounding “no.” They’re 14th in walk rate and 12th in avoiding chases. They’re 17th in runs per game while they’re 13th in homers and 17th in ISO, so it doesn’t look like they’re doing anything special. Have they gained any magical benefit from their attempts to do whatever it is they’re doing? Nope.

If you wanted to be generous, you could say they got better at moving a leadoff double to third. Maybe. Sorta. The team the Braves assembled has never been good at situational hitting. They were good at homers. Now they’re not good at homers, and also not good at situational hitting (unless you need a runner moved to third, I guess). All the other stuff that people like to talk about mattering to swing games (even though they’re wrong)? Also not improved. The team has worse batting results with RISP than without RISP; it has a 110 wRC+ in low leverage, 90 in medium leverage, and 88 in high leverage. “The 2025 Atlanta Braves: we are good at defense and hitting in low leverage” is not much of a slogan.

Nor are the Braves good at other offensive things on the margins. They are literally league average in setting up the platoon advantage for their bats via lineup construction or pinch-hitting. Speaking of pinch-hitting: the team desperately wants to find playing time for both Sean Murphy and Drake Baldwin, while having a rotating cast of third outfielders, yet is 23rd in pinch-hitting frequency. They’re bottom ten in infield hits, have an average number of bunt hits, and are 14th in sacrifice bunt tries while having the sixth-worst success rate. They are average at their rate of hitting into double plays. They are average on the bases — it doesn’t get more generic than “number of runs gained from advances is exactly offset by number of runs lost from getting thrown out or choosing not to advance.” For a team that claims to want to do everything offensively to some degree of usefulness, the Braves just haven’t. Whether it’s a personnel issue, a spread-too-thin issue, a commitment issue, or whatever else, it just kind of reads as executive dysfunction, Sure, they may want to do things like “be aggressive and put pressure on the defense” and “have productive at-bats” in theory, but in practice, they’re not really capable of doing those things in any way that’s useful.

Part of the issue is that the Braves’ spare parts, “different ways,” approach doesn’t actually work mathematically. Dave Cameron did this back in 2015 and found that lower-OBP, higher-SLG teams benefit from more lower-OBP sluggers, while higher-OBP, lower-SLG teams benefit from keeping the line moving. You can read the article, and this pseudo-update from Ben Clemens in 2021 (during the actual juiced ball era, given that that would probably influence Cameron’s results…), and see that, well, trying to add on-base-only guys like Alex Verdugo, and trading slugging for on-base doesn’t actually work that well when your lineup already has entrenched slugging guys. Or, more accurately: you’d just be better off adding more slugging.

To wit: the Braves are 16th in batting runs, but 22nd in RE24. Neither is good, and some of that gap could just be random variation, but I checked and in the Braves’ case, it isn’t really — basically the idea is that the Braves are less than the sum of their parts, because they have neither the power to consistently score with one swing, with an occasional multiplier from a previous baserunner, yet also lack the OBP to chain non-outs into runs. The difference isn’t huge — I calculate it as about a win right now through 52 games, based on their 4.38 BaseRuns-estimated runs per game and their actual 4.15 runs per game — but the point is less about giving up another win from the types of replacements they’ve been forced to use, and more that morphing free-swinging sluggers into walk machines doesn’t even work that well unless all your sluggers turn into walk machines. The bar for success was pretty high, and in practice, the Braves’ attempts to remake themselves offensively looks something like them forgetting they were doing the hurdles event in the first place.

If you want to feel optimistic, go look at what Ozuna and Olson have done, and beseech whatever deity you still believe in that Ronald Acuña Jr. either avoids changing like his teammates, or takes to it like Ozuna and Olson have. You could also hope that things just magically click within the next week and the Braves conduct a very hungry caterpillar-esque metamorphosis into the current Yankees (low chase, high walks, high power), but they really don’t have much more time to work through it without the season slipping away from them. (And, again, it’s not like this is has been a dedicated, constant thing. I’m not sure whether that makes it more or less frustrating.)

The pitching (and the homers)

The story of the pitching thus far has basically been the story of giving up homers. The good news: the HR/FB will probably regress. The bad news: the pitching has been meh even if it does.

Of their 13 most-used arms so far (adding Bryce Elder to the mix of current rostered pitchers), only six have an FIP- and xFIP- below 100, and one of them is Spencer Schwellenbach, who gave up two homers to lefties the third time through in his last start and may see that FIP creep up further if that continues. Aaron Bummer, Pierce Johnson, and Chris Sale are the only two who A) are pitching great and B) aren’t getting victimized by HR/FB. On the flip side, the Braves have five guys (Grant Holmes, Elder, Dylan Lee, Scott Blewett, and Raisel Iglesias) who have pitched okay and gotten absolutely bombed by homers — and then Rafael Montero and Daysbel Hernandez, who have honestly been the bad kind of pants but no one’s homered off them so it doesn’t seem nearly as horrible in the moment. Going forward, is an average pitching contribution going to be enough? Not with whatever’s going on offensively, as described above. The pitching was a hard carry for the team amid barreled out problems last year, but I don’t think the Braves can survive the dual problems of “team is not hitting homers” and “pitching may not give up as many homers going forward, but already shed a bunch of playoff odds because it gave up a ton of homers over the past two months.”

It’s tempting to say that part of the Braves’ issue has been giving up homers at the worst possible times, but that’s actually not really the case. If you go back and look at the leverage or context in which the Braves have given up homers, whether you do so by using WPA or just RE24 (which includes base-out state but not the score or the inning), the Braves have actually been fortunate to give up homers of average costliness to win expectancy overall. So, even if they give up fewer homers altogether, there probably won’t be a huge boost there. There’s also likely going to be a debit the other way when the poor peripherals catch up to Montero and Hernandez, even as they continue to work in higher leverage than, say, Bummer. Sure, maybe those guys actually improve their peripherals, but that doesn’t seen any more likely than the Braves paying the price for sticking with them.

Where can they find a boost? It seems silly to talk about because we know they won’t, but, once again, the Braves find themselves in a situation where they’re third-to-last in bullpen appearances, dead last in bullpen innings and bullpen batters faced, yet are top ten in having pitchers face batters at least three times. They also have the tenth-worst FIP in the process. Now, you could say, well, they have the tenth-best xFIP, so it’s a HR/FB problem for them the third time through rather than a performance problem, and you’d have a point, except that HR/FB tends to increase with times through the order. Your point would also be undermined by the fact that the Braves are much, much worse in non-low leverage the third time through than they have been otherwise, while still being in the top ten in the number of those situations they face. There’s an improvement there, but the team has no interest in taking it.

The past

In recent history, we’ve seen two Braves teams come out of the gate struggling, but ultimately have a rewarding season: the 2021 and 2022 squads. Meanwhile, the 2024 squad was mired in an unfortunate three-month run from May through July; we can throw them in too just to hammer a point home.

The 2021 team famously did not clear .500 for good until early August. However, despite the issues with its record, it was seventh in position player value and 14th in pitching value to that point. It was underperforming its WAR by about four wins by the time it reached .500 for the final time on August 5. It’s a common misconception that the team somehow played super-well down the stretch. Instead, what they did was win super-well down the stretch. They ranked 12th and 13th in position player value and pitching value, respectively, as they went 33-18 over their final 51 games. However, they crammed in a stunning +5 extra wins in that seven-week period. Without that, they only make the playoffs because the Phillies finished at 82-80, and given that they swept the Phillies late in the year and only finished 10-9 against them overall, you get the idea. The point is that they were pretty good and unlucky for much of the year, and then meh and very lucky to win all those games.

The 2022 team looked moribund until a 14-game winning streak at the start of June following a walkoff loss in Arizona catapulted their season towards “awesome.” Through May, the team was 13th in hitting value and eighth in pitching value; they were four wins short of their “deserved” win total even before the winning streak (should’ve been 27-23, instead were 23-27).

From May 1 through July 31 in 2024, the Braves went 39-40. They did so with the league’s third-best pitching performance and its 13th-best hitting performance. That’s not play that corresponds to being a game below .500. Again, we’re talking outputs here, and hopefully you get the idea. All of the team’s prior struggles for extended stretches in this decade? They came from a lack of wins, not from a lack of production.

Before they hit .500 for the final time on August 5, the 2021 Braves were fifth in MLB in xwOBA. However, they had the sixth-biggest underperformance. (Note: this is a totally different measure of “fortune” than the prior paragraphs. This is about inputs not translating into outputs, the above paragraphs are about outputs not translating into wins.) The 2021 team looked screwed because of where it was in the standings, not because of what the players were doing.

Through May, the 2022 Braves had a middling wOBA, the league’s seventh-best xwOBA, and you guessed it, the sixth-biggest underperformance. 2022 was a reversion to a much draggier ball from what transpired in 2021, but in the summer, with the added boost to airball distance, the Braves rode a top-two wOBA and xwOBA mark, thanks to a lack of underperformance, to that epic season. (The 2022 Braves were also helped early on by a lack of HR/FB against them, but were clearly able to weather the storm once the temperatures increased.)

That 2024 three-month stretch, well, we maybe could say it started this whole mess. Maybe. The team wasn’t exactly blasting the cover off the ball — 12th in xwOBA, the injuries have to be kept in mind — but it had the biggest xwOBA underperformance of any team in that span, leading to what looked like (but was not) a offense suffering from anemia. The offense improved in August and September (sixth in xwOBA), but it also stopped getting screwed on balls in play (no underperformance, hence sixth-best wOBA), and the Braves salvaged the season (albeit barely).

The present

At this point, you probably get where this section is going. The stuff above doesn’t apply to the 2025 Braves. They’re right around league average in wOBA (14th) and xwOBA (13th). There’s no underperformance there. Nor are they losing games because the production just isn’t working: they have the same number of wins their WAR suggests they should. BaseRuns has them at 26-27 instead of 25-28, but that’s still under .500 and nowhere near playoff position. They’re underplaying their run differential by three games, but their run differential is still 16th-best in MLB. There’s no there there, not like those other teams, at least not right now.

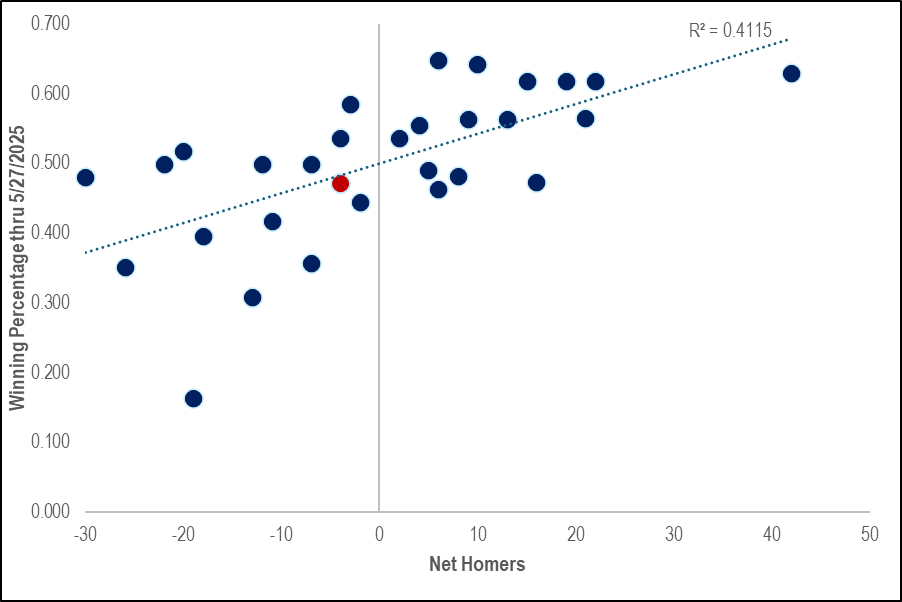

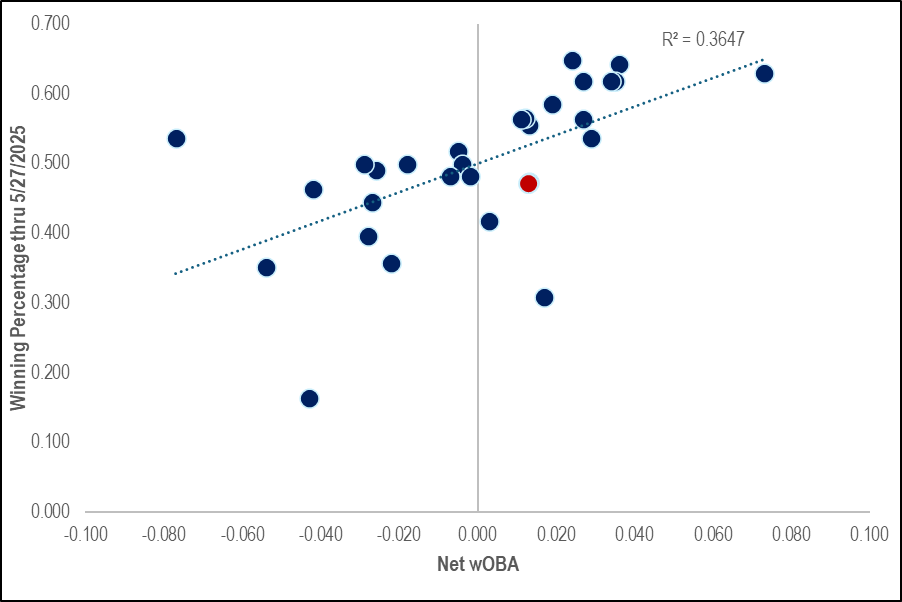

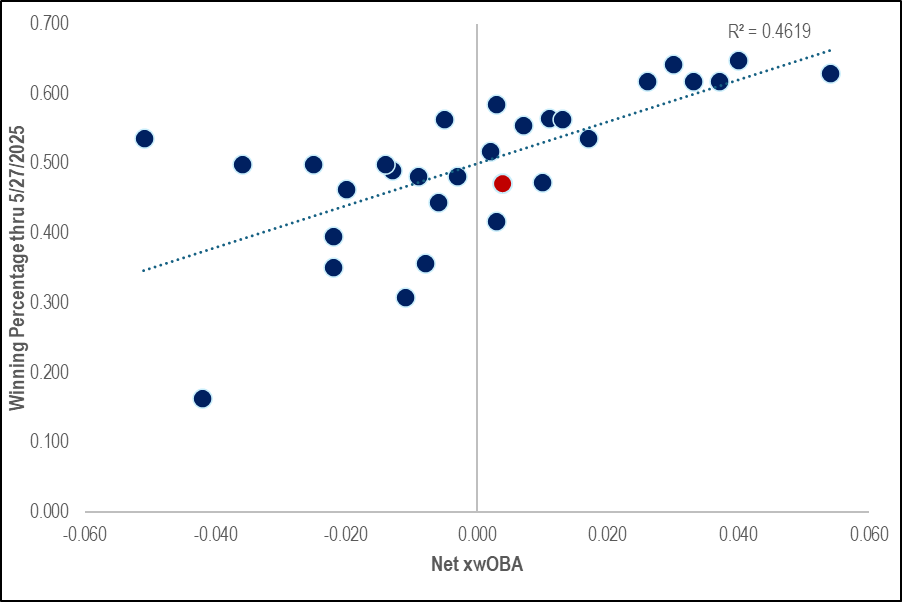

Nor is this some kind of specific single-game quirk adding up over two months of games. Every day, I track every game in terms of whether the winner outhomered the loser, out-wOBAed them, and out-xwOBAed them. (Note: the xwOBA element ignores defense, which the Braves have been good at.) If you got a win every time you outhomered a team and the rest were randomly assigned, the Braves would be… 25-28. If you got a win every time you wOBAed a team, the Braves would be 24-29. If you got a win every time you out-xwOBAed a team, the Braves would be 27-26. Hang on to that last one, folks — that’s all the Braves have right now.

Here’s the plot of net homers — it’s pretty remarkable that we’re just about a third of the way through the season and net homers already explain 40 percent of the variation in team record — and the conclusion is that the Braves need to either hit more homers or yield fewer, preferably both at the same time.

Here’s the plot of net wOBA — the good news is that it suggests the Braves should be better than they are, but like run differential, we’re still talking MLB’s 16th-best team in this regard.

And finally, net xwOBA, whose R-squared is approaching 50 percent even though we’re not even out of May yet. No, the Braves aren’t good enough here, either.

The rest of the season

I could’ve saved you the last 4,200 words: the Braves need to play better. They need to hit more homers and allow fewer homers. To do that, they likely need to do things that actually help with hitting homers (swinging harder/faster, swinging at strikes). If they’re not going to hit more homers, then they need to allow fewer homers and get better at the other stuff. But, they’ve shown little interest in improving their pitching management, and two months in, they don’t seem to actually be any good at the other stuff as a team.

The 2021 team had trouble translating production into wins for four months, got a windfall of extra wins over the final two months, and made hay with it. The 2022 team couldn’t deal with the draggier ball to clobber opponents into submission for two months, but then started doing so and turned the season into an epic division chase. The 2024 team was seemingly cursed for three straight months but rode their pitching and said curse’s eventual lifting to a playoff berth amid a bunch of injuries. The 2025 team can add its own “X but then Y” statement here, but they’ll need to do something — but “the 2025 Braves undermined their own talent for at least half the season” is not a fragment that is likely to have a happy conclusion.

Ever since 2018, that magical season where the Braves turned playoff odds of three percent into a division title, you could be waiting for the other shoe to drop — when is the universe going to get back at those audacious 2018 boys and their Johan Camargo-ing? It could’ve happened last year, with all those injuries, the extremely draggy ball and the subsequent underperformance, and so on. If the Braves ended up with a lost season, it would’ve sucked, but the karmic bill coming due after six years, well, it happens. This season, though? That’s no karmic bill, that’s the Braves themselves. They’ve got two-thirds of the season left. Time to draw on the recent past and channel those past six years, because there’s no secret underperformance that’s going to right itself, no “well, actually they’re fine and unlucky and it’s a long season to lean on.”

It’s a different year with different, self-inflicted challenges. The bad news? No correction is coming to save the Braves. The good news? They’re the furthest thing from helpless. They can save themselves.